2005 STRINGFELLOW

This ecumenical, inclusive event marked the 20th anniversary of the death of Stringfellow, a lay theologian whose grasp of the Powers and Principalities continues to shape radical discipleship and resistance in an age of renewed empire. We experimented with the concept of Biography as Theology as we celebrated Stingfellow’s life and legacy.

We joined together for Bible study, social

analysis, worship, and conversation (Rose Berger leading worship at right).

We gathered around beloved friends in a healing circle (below) as we honored our own stories of struggle and pain, and we brought Stringfellow’s legacy and work into conversation with a new generation of activists.

Components:

analysis, worship, and conversation (Rose Berger leading worship at right).

We gathered around beloved friends in a healing circle (below) as we honored our own stories of struggle and pain, and we brought Stringfellow’s legacy and work into conversation with a new generation of activists.

Components:

- Who Was William Stringfellow

- Stringfellow Courses and Faculty

- Worship and Prayer

- The Circus by William Stringfellow

- Circus Theology by Kate Foran

WHO WAS WILLIAM STRINGFELLOW?

Theological critic of Imperial America; reviver of biblical theology and ethics with reference to the “principalities and powers;” civil rights activist helping goad white mainstream Christianity into the black freedom struggle of the sixties; participant in post-WWII ecumenism, helping shape the worldwide student Christian movement; 1956 Harvard Law School graduate who took up street law in New York’s East Harlem; early critic of the Vietnam war visiting there in 1966; notorious interlocutor with Karl Barth in his 1962 visit to the States; friend, counsel, and biographer of Bishop James Pike; federal indictee charged with harboring Daniel Berrigan while underground in August of 1970; founder of the underground seminary; correspondent of Jacques Ellul; subject of FBI surveillance; advisor and canonical defender of the Episcopal women priests irregularly ordained in 1974; caller for the impeachment of Richard Nixon (well before Watergate); reformer and environmental activist in the small town politics of Block Island; connoisseur of the circus; host and cook extraordinaire; “monastic” contemplative and island recluse; author of sixteen books…

… Parable of the Word of God.

… Parable of the Word of God.

STRINGFELLOW COURSES AND FACULTY

Following is a list of the Stringfellow Word and World faculty and classes offered:

Morning Bible Studies

Morning Bible Studies

John 1: Neil Elliot

Genesis 4: Liz McAlister

Jeremiah 29: Uncas McThenia

Genesis 10-11: Ched Myers

Romans 13: Will O’Brien

Colossians 1:15-20: Bill Wylie-Kellermann

Matthew 13: Laurel Dykstra

Hebrews 11: Joyce Hollyday

Revelation 13: Will O’Brien

Isaiah 14: Ched Myers

Acts 3-5: Bill Wylie-Kellermann

Afternoon Courses

Participatory Resurrection: Anthony Towne: Rose Berger

Beyond the Binary Anthony Dancer: Vocation as Ethics Scott Kennedy: Stringfellow and Nonviolence Carmen Lane: Sexual Identity and Conversion : James Breeden

Biography as Theology Jacob Brown: A New Generation reads Stringfellow: Bill Wylie-Kellermann and Uncas McThenia

Empire and Resistance: Liz McAllister

Stringfellow and the Law: Uncas McThenia

The Circus as Kingdom: Ched Myers, Laurel Dykstra, and Kate Foran

The Underground Seminary: Bill Wylie-Kellermann

WORSHIP AND PRAYER

Reading America Biblically: The Stringfellownian Task and The Powers, Vocation, and Labor with music by Ray Makeever

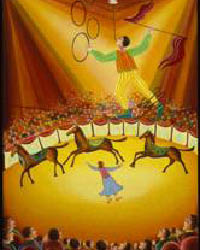

THE CIRCUS BY WILLIAM STRINGFELLOW

From Simplicity of Faith, 1982, pp. 87-91

It is only since putting aside childish things that it has come to my mind so forcefully — and so gladly — that the circus is among the few coherent images of the eschatological realm to which people still have ready access, and that the circus thereby affords some elementary insights into the idea of society as a consummate event. This principality, this art, this veritable liturgy …this common enterprise of multifarious creatures called the circus, enacts a hope, in an immediate and historic sense, and simultaneously embodies an ecumenical foresight of radical and wondrous splendor, encompassing, as it does both empirically and symbolically, the scope and diversity of Creation.

I suppose some - ecclesiastics or academics or technocrats or magistrates or potentates - may deem the association of the circus and the Kingdom scandalous or facetious or bizarre, and scoff quickly at the thought that the circus is relevant to the ethics of society. Meanwhile, some of the friends of the circus may consider it curious that during intervals when Anthony and I have been their guests and, on occasion, confidants, that I have had theological second thoughts about them and about what the corporate existence of the circus tells and anticipates in an ultimate sense. To either I only respond that the connection seems to me to be at once suggested when one recalls that biblical people, like circus folk, live typically as sojourners, interrupting time, with few possessions, and in tents, in this world. The Church would likely be more faithful if the Church were similarly nomadic.

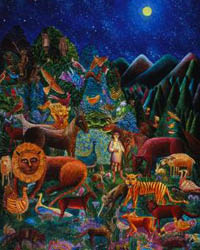

In America, during the earliest part of this century, the circus enjoyed a "golden age." It was the era of P.T. Barnum, Adam Fourpaugh, and the Ringling Brothers, to name but a few of the showmen who assembled extraordinary aggregations of performers, animals and oddities. It was then that the circus was most lucidly an image of the Kingdom in its magnitude, versatility and logistics. There were, for example, few permanent zoological collections in those days, and the circus menagerie was the opportunity for people to see rare birds and reptiles, exotic animals and mammals, wild beasts and other marvelous creatures. Indeed, when the Ringling Brothers advertised their "mammoth millionaire menagerie" as the "greatest gathering since the deluge" it was not a much exaggerated boast.

It is only since putting aside childish things that it has come to my mind so forcefully — and so gladly — that the circus is among the few coherent images of the eschatological realm to which people still have ready access, and that the circus thereby affords some elementary insights into the idea of society as a consummate event. This principality, this art, this veritable liturgy …this common enterprise of multifarious creatures called the circus, enacts a hope, in an immediate and historic sense, and simultaneously embodies an ecumenical foresight of radical and wondrous splendor, encompassing, as it does both empirically and symbolically, the scope and diversity of Creation.

I suppose some - ecclesiastics or academics or technocrats or magistrates or potentates - may deem the association of the circus and the Kingdom scandalous or facetious or bizarre, and scoff quickly at the thought that the circus is relevant to the ethics of society. Meanwhile, some of the friends of the circus may consider it curious that during intervals when Anthony and I have been their guests and, on occasion, confidants, that I have had theological second thoughts about them and about what the corporate existence of the circus tells and anticipates in an ultimate sense. To either I only respond that the connection seems to me to be at once suggested when one recalls that biblical people, like circus folk, live typically as sojourners, interrupting time, with few possessions, and in tents, in this world. The Church would likely be more faithful if the Church were similarly nomadic.

In America, during the earliest part of this century, the circus enjoyed a "golden age." It was the era of P.T. Barnum, Adam Fourpaugh, and the Ringling Brothers, to name but a few of the showmen who assembled extraordinary aggregations of performers, animals and oddities. It was then that the circus was most lucidly an image of the Kingdom in its magnitude, versatility and logistics. There were, for example, few permanent zoological collections in those days, and the circus menagerie was the opportunity for people to see rare birds and reptiles, exotic animals and mammals, wild beasts and other marvelous creatures. Indeed, when the Ringling Brothers advertised their "mammoth millionaire menagerie" as the "greatest gathering since the deluge" it was not a much exaggerated boast.

"This is our camp, our moving city; each day we set the show up: jugglers calm amid currents, riding the world, joggled but slightly as in a howdah, on the grey wrinkled earth we ride as on an elephant’s head. " |

It was similar with the "sideshows" or "museums" traditionally associated with the American circus. A separate feature from the main circus performance, the side show originated with Barnum. It assembled and exhibited human "oddities" and "curiosities" - giants, midgets, and the exceptionally obese; Siamese twins, albinos, and bearded ladies; those who had rendered themselves unusual like fire eaters, sword swallowers, or tattooed people. If the side show seems macabre because "freaks" were sometimes exploited, it must also be mentioned that in those days little medical help and few other means of livelihood were available to such persons and that the premise of these exhibits was educational. In any case, so long as they continued they symbolized the circus as an eschatological company in which all sorts and conditions of life are congregated.

It is in the performance that the circus is most obviously a parable of the eschaton. It is there that human beings confront the beasts of the earth and tame them. The symbol is magnified, of course, when one recollects that, biblically, the beasts generally designate the principalities: the nations, dominions, thrones, authorities, institutions, and regimes.

There, too, in the circus, humans are represented as freed from consignment to death. There one person walks a wire fifty feet above the ground, another stands upside down on a forefinger, another juggles a dozen incongruous objects simultaneously, another hangs in the air by the heels, one upholds twelve in a human pyramid, another is shot from a cannon. The circus performer is the image of the eschatological person - emancipated from frailty and inhibition, exhilarant, militant, transcendent over death - neither confined nor conformed by the fear of death any more. The eschatological parable is, at the same time, a parody of conventional society in the world as it is. In a multitude of ways in circus life the risk of death is bluntly confronted and the power of death exposed and, as the ringmaster heralds, defied. Clyde Beatty, at the height of his career, actually had forty tigers and lions performing in one arena. The Wallendas, not content to walk the high wire one by one, have crossed it in a pyramid of seven people. John O'Brien managed sixty-one horses in the same ring, in what a press agent called "one bewildering act". Mlle. La Belle Roche accomplished a double somersault at great speed and height in an automobile at the time when autos were still novelties. Moreover, the circus performance happens in the midst of a fierce and constant struggle of the people of the circus, especially the roustabouts, against the hazards of storm, fire, accident, or other disaster, and it emphasizes the theological mystique of the circus as a community in which calamity seems to be always impending. After all, the Apocalypse coincides with the Eschaton.

Meanwhile, the clowns make the parody more poignant and pointed in costume and pantomime; commenting, by presence and performance, on the absurdities inherent in what ordinary people take so seriously - themselves, their profits and losses, their successes and failures, their adjustments and compromises - their conformity to the world.

So the circus, in its open ridicule of death in these and other ways - unwittingly, I suppose - shows the rest of us that the only enemy in life is death, and that this enemy confronts everyone, whatever the circumstances, all the time. If people of other arts and occupa tions do not discern that, they are, as Saint Paul said, idiots. (cf.; Ephesians 4:17-18).

The service the circus does - more so, I regret to say, than the churches do - is to openly, dramatically, and humanly portray that death is in the midst of life. The circus is eschatological parable and social parody: it signals a transcendence of the power of death, which exposes this world as it truly is while it pioneers the Kingdom.

Ever since the creation of the world his eternal power and divine nature, invisible though they are, have been understood and seen through the things he made. So they are without excuse; for though they knew God, they did not honor him as God or give thanks to him, and they became futile in their thinking, and their senseless minds were darkened. Claiming to be wise, they became fools. Our dreams have tamed the lions, have made pathways in the jungle, peaceful lakes; they have built new Edens ever sweet and ever changing. By day from town to town we carry Eden in our tents and bring its wonders to the children who have lost their dream of home. |

CIRCUS THEOLOGY BY KATE FORAN

AEditor's Note: Kate Foran served as an intern and staff for Word and World from July 2004 through January 2006. She and her partner Steve lived with the Voluntown Peace Trust in rural Connecticut.

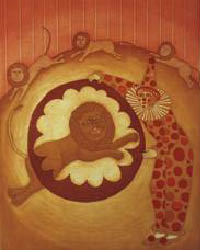

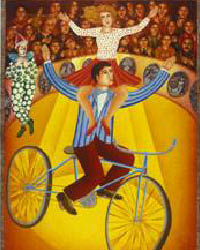

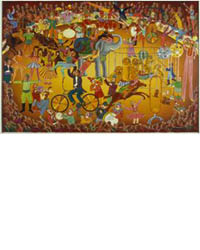

In a time when “circus” is likely to conjur images of animal cruelty and overcrowded city civic centers, it is hard to imagine that the performance of that spectacle could be likened to the in-breaking of the Kingdom of God. At least, it was hard for me to imagine, until I learned to see the circus through the eyes of the lay theologian William Stringfellow, the poet Robert Lax, and the artist John August Swanson. The discipline of attending to the world—in the circus and elsewhere—for evidence of Grace practiced by these three helped me open my eyes to transformative moments around me.

When Word and World decided to undertake a weekend school exploring the life and work of William Stringfellow, we discovered that one of the benefits of basing a school on one person’s biography is the light we shed on obscure corners of a life. For instance, where Stringfellow is known, he is generally known as a lay theologian, author, and street lawyer. But he was also a connoisseur of the circus. He collected memorabilia, photographs, even the autograph of lion tamer Clyde Beatty. Some who knew him recount that he would accept speaking engagements on the basis of whether the circus was in town. He understood the circus, as he interpreted most everything, Biblically. In Stringfellow’s musings on the circus, he explains the circus as a liturgy, a nomadic community, and a peaceable kingdom where lions are tamed and people of all sorts are gathered. It is a spectacle, but it invites participation. According to Stringfellow, the transient nature of the circus, along with its color, bombast, and death defying acts, all offer insight into the eschatalogical realm of the coming of God.

Stringfellow was not alone among his contemporaries in this idea. Poet Robert Lax (friend of Thomas Merton) also followed the circus, and wrote a series of poetry about his experience. For Lax, who watched the circus folk set the tents up and tear them down, and who watched the acrobats fumble and get up again until ready for performance, the circus represented a creation story as well as a parable of Death and Resurrection. Artist and activist John August Swanson, best known for his serigraph images of Biblical narratives, has also drawn on images of the circus to explore themes of how we enter the “sacred circle” to participate in the balancing act that is the community of creation. All three share a conviction that perhaps, with its performance of a living Word transcendent over the powers of oppressive social norms, cynicism, and death— the circus was in fact more church than church. In this way, their writing, poetry, and art puts in one ring the images of clowns and priests; wandering nomads and circus parades. It juggles together both acrobats and angels; tents and tabernacles; lion tamers and peaceable kingdoms; theology and three ring extravaganzas. And the circus images begin to blur with the theological ones at precisely the point of vulnerability where discipline becomes Grace.

Discipline and Grace: it is the balancing act on the unicycle; the swinging acrobat whose muscles have memorized the moment to let go. It is God’s economy, the tightrope tension between limits and abundance: the manna stories of reliance on God for sustenance, the discipline required in the communal practice of gathering just enough, and the bounty that rains down.

Study of Stringfellow’s circus theology, Lax’s poetry, Swanson’s art, along with scripture, is much the same: it challenges me to comb through the stories, attentive, disciplined, receptive. Stringfellow’s passion for the circus also urged me to identify where else we might find this kind of “circus theology” of restraint and extravagance. In seeing the circus as a kind of controlled calamity that recreates the order of the everyday world, I think of Dorothy Day, a founder of the Catholic Worker movement, who was a child in San Francisco when the real disaster of the 1906 earthquake turned that city upside down. She spent the rest of her life trying to recreate and embody the spirit of community and mutual aid that arose in the first moments following the catastrophe. It’s as if her disciplines of hospitality to the poor and resistance to violence were the acrobat’s preparation--the practice for, the practice of, the Grace that overtakes you, the Kingdom breaking in.

At least I know that this readiness is what I often find at the Beloved Community’s Homeless Hospitality House, where pecans fall from the trees and people without homes or jobs show me where to gather them. Indeed, to spend time with the newly born, or those facing death, or people struggling with addiction, or people walking in an economic lion’s den is to draw near to the same mystery Stringfellow found in the circus. It is to face, as Stringfellow notes, the reality of our precariousness—which is to make us aware of our need for God—which is finally to resist death’s hold.

In a time when “circus” is likely to conjur images of animal cruelty and overcrowded city civic centers, it is hard to imagine that the performance of that spectacle could be likened to the in-breaking of the Kingdom of God. At least, it was hard for me to imagine, until I learned to see the circus through the eyes of the lay theologian William Stringfellow, the poet Robert Lax, and the artist John August Swanson. The discipline of attending to the world—in the circus and elsewhere—for evidence of Grace practiced by these three helped me open my eyes to transformative moments around me.

When Word and World decided to undertake a weekend school exploring the life and work of William Stringfellow, we discovered that one of the benefits of basing a school on one person’s biography is the light we shed on obscure corners of a life. For instance, where Stringfellow is known, he is generally known as a lay theologian, author, and street lawyer. But he was also a connoisseur of the circus. He collected memorabilia, photographs, even the autograph of lion tamer Clyde Beatty. Some who knew him recount that he would accept speaking engagements on the basis of whether the circus was in town. He understood the circus, as he interpreted most everything, Biblically. In Stringfellow’s musings on the circus, he explains the circus as a liturgy, a nomadic community, and a peaceable kingdom where lions are tamed and people of all sorts are gathered. It is a spectacle, but it invites participation. According to Stringfellow, the transient nature of the circus, along with its color, bombast, and death defying acts, all offer insight into the eschatalogical realm of the coming of God.

Stringfellow was not alone among his contemporaries in this idea. Poet Robert Lax (friend of Thomas Merton) also followed the circus, and wrote a series of poetry about his experience. For Lax, who watched the circus folk set the tents up and tear them down, and who watched the acrobats fumble and get up again until ready for performance, the circus represented a creation story as well as a parable of Death and Resurrection. Artist and activist John August Swanson, best known for his serigraph images of Biblical narratives, has also drawn on images of the circus to explore themes of how we enter the “sacred circle” to participate in the balancing act that is the community of creation. All three share a conviction that perhaps, with its performance of a living Word transcendent over the powers of oppressive social norms, cynicism, and death— the circus was in fact more church than church. In this way, their writing, poetry, and art puts in one ring the images of clowns and priests; wandering nomads and circus parades. It juggles together both acrobats and angels; tents and tabernacles; lion tamers and peaceable kingdoms; theology and three ring extravaganzas. And the circus images begin to blur with the theological ones at precisely the point of vulnerability where discipline becomes Grace.

Discipline and Grace: it is the balancing act on the unicycle; the swinging acrobat whose muscles have memorized the moment to let go. It is God’s economy, the tightrope tension between limits and abundance: the manna stories of reliance on God for sustenance, the discipline required in the communal practice of gathering just enough, and the bounty that rains down.

Study of Stringfellow’s circus theology, Lax’s poetry, Swanson’s art, along with scripture, is much the same: it challenges me to comb through the stories, attentive, disciplined, receptive. Stringfellow’s passion for the circus also urged me to identify where else we might find this kind of “circus theology” of restraint and extravagance. In seeing the circus as a kind of controlled calamity that recreates the order of the everyday world, I think of Dorothy Day, a founder of the Catholic Worker movement, who was a child in San Francisco when the real disaster of the 1906 earthquake turned that city upside down. She spent the rest of her life trying to recreate and embody the spirit of community and mutual aid that arose in the first moments following the catastrophe. It’s as if her disciplines of hospitality to the poor and resistance to violence were the acrobat’s preparation--the practice for, the practice of, the Grace that overtakes you, the Kingdom breaking in.

At least I know that this readiness is what I often find at the Beloved Community’s Homeless Hospitality House, where pecans fall from the trees and people without homes or jobs show me where to gather them. Indeed, to spend time with the newly born, or those facing death, or people struggling with addiction, or people walking in an economic lion’s den is to draw near to the same mystery Stringfellow found in the circus. It is to face, as Stringfellow notes, the reality of our precariousness—which is to make us aware of our need for God—which is finally to resist death’s hold.